For decades, one of the greatest technical barriers in computing was the language gap. Humans communicate through words, which are inherently rich, nuanced, and context-dependent. Computers, conversely, process the world exclusively through precise, numerical data. By mapping concepts to coordinates, computers can finally understand that "happy" and "joyful" are close neighbors, while "happy" and "sad" are distant opposites.

The Shift from Symbol Matching to Geometry

To grasp why embeddings are revolutionary, we first need to look at the limitations of previous methods. Traditional databases utilized lexical search. If you typed "jacket" into a search bar, the system merely scanned its index for the exact character string "j-a-c-k-e-t."

This approach is fundamentally brittle and fails to capture user intent. If a customer searches for "warm winter coat," the system might miss an item labeled "heavy thermal jacket" simply because the vocabulary doesn't match, even though the concepts are functionally identical. The computer treats words as arbitrary, unrelated symbols.

Embeddings solve this by moving away from matching symbols and toward matching semantics (meanings). The entire problem is recast from a linguistic search into a geometry problem.

Vectorization: Converting Concepts into Coordinates

At its core, an embedding is a vector. Mathematically, a vector is simply an ordered array of numbers, which serves as a set of coordinates on a conceptual map.

Imagine a highly simplified two-dimensional map used to describe cars. You could plot different models based on two core features: "Speed" (x-axis) and "Off-Road Capability" (y-axis).

- A Sports Car might be at coordinates [10, 1] (High Speed, Low Off-Road).

- A Jeep might be at [3, 9] (Low Speed, High Off-Road).

- A Sedan might be at [5, 5] (Moderate Speed, Moderate Off-Road).

In this map, the computer can instantly calculate the physical distance between the points. It can see that the "Sports Car" point is statistically distant from the "Jeep" point. Without knowing anything about engines or tires, the system understands their profiles are dissimilar.

Real-world embeddings, however, don't just use two dimensions. They use hundreds or even thousands. A modern language model might map a single word to a vector with 1,536 dimensions. Each dimension represents a subtle, learned characteristic of that word. One dimension might vaguely represent "formality," another "physicality," and another "temporal relevance."

When a word or a sentence is processed, it is assigned a specific list of thousands of numbers. The crucial insight is that concepts with similar meanings end up with numerical vectors that are similar.

- Monarch: [0.8, 0.2, 0.9, ...]

- Ruler: [0.7, 0.2, 0.8, ...]

Because the numerical arrays are statistically similar, the distance between them in this multi-dimensional space is tiny. The computer interprets this proximity as semantic similarity.

The Power of Conceptual Arithmetic

Because embeddings encode meaning as position and relationship as direction, they allow for sophisticated mathematical operations on abstract concepts.

A famous demonstration of this principle involves the relationship between royalty and gender. If you take the vector for King, subtract the vector for Man, and add the vector for Woman, the resulting set of numbers lies almost exactly at the location of the vector for Queen.

This ability to navigate concepts spatially is what allows modern automated systems to understand analogies, perform logical inferences, and hold coherent, context-aware conversations.

Addressing Ambiguity: Contextual Embeddings

A major challenge in language is polysemy—the fact that words change meaning based on surrounding context. The word "bank" means something entirely different in "bank of the river" versus "bank of America."

Early embedding models assigned a single, static vector to every word, which was a clear limitation. Modern systems utilize contextual embeddings. They do not just process the single word; they process the entire surrounding phrase. The system looks at nearby words ("river" versus "America") to dynamically adjust the vector for the ambiguous word.

Applications Across Digital Infrastructure

The utility of embeddings extends far beyond defining individual words. They are the engine behind many of the "smart" features that define the modern digital experience.

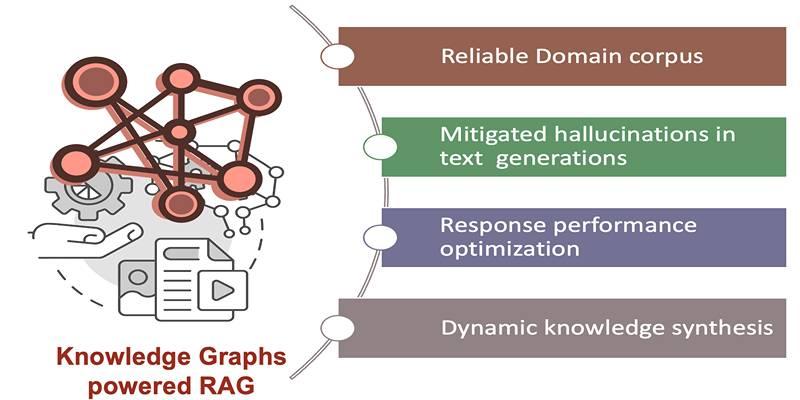

Semantic Search

This directly replaces the old keyword approach. When a user types a query into a search engine, the system converts that entire query into a vector. It then looks for documents in its database that are "close" to that query vector, mathematically. This allows the system to match the intent ("how to fix a flat tire") to the content ("repairing punctured bicycle wheels"), regardless of the specific vocabulary used.

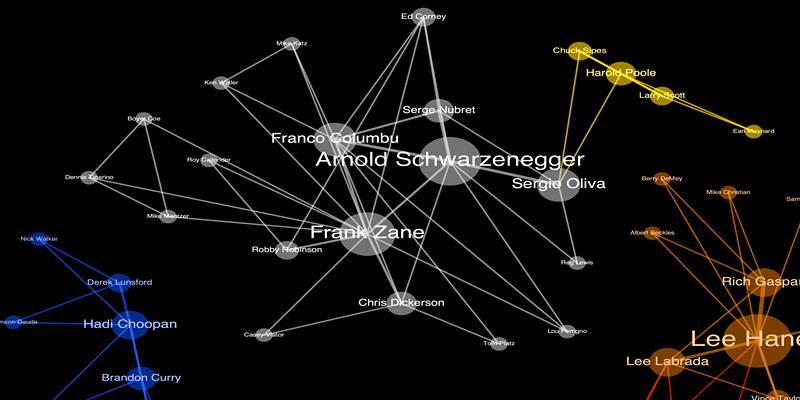

Recommendation Engines

Streaming services and e-commerce sites use embeddings to maintain engagement. They don't just embed words; they embed user behavior and content profiles.

- A user's history and preferences are compiled into a single user vector.

- A new song or movie is mapped into a vector based on its genre, plot, and emotional tone.

If the user's vector is mathematically close to a new movie's vector, the system predicts a high likelihood of enjoyment. It is the exact same geometric principle: finding statistically likely neighbors in a multi-dimensional space.

Classification and Content Moderation

Embeddings simplify the process of sorting vast amounts of data. To build a spam filter, an incoming email is converted into a vector. If that vector lands in a region of the mathematical space known to be heavily populated by "spam" vectors, the system automatically flags it. This is far more resilient than blocking specific words, which spammers can easily bypass by misspelling them.

Conclusion: The Bridge to Conceptual Understanding

Embeddings represent a fundamental, necessary shift in how software interacts with the world. We have moved from a world of rigid rules and exact matches to a world of statistical relationships and conceptual proximity.

Translating the messy, unstructured reality of human communication into the structured, precise language of vector mathematics, we have given computers a pathway to interpret meaning, context, and intent. This numerical foundation is the invisible geometry of thought that underpins the most complex and adaptive capabilities of the modern digital landscape.