The introduction of sophisticated computational systems into the workplace is frequently framed as a zero-sum equation: jobs lost versus jobs gained. Economic history, however, suggests the reality is far more complex and paradoxical. Advanced automation simultaneously renders certain tasks obsolete while creating entirely new classes of work, fundamentally reorganizing the structure of the labor market rather than simply diminishing its size. The primary effect is not job replacement, but a rapid, often painful, re-tasking of human capital.

Concerns about technology eliminating the need for human labor are not new; such fears date back to the Luddites and were popularized by John Maynard Keynes, who termed it "technological unemployment." The current wave of automation, driven by probabilistic models, is unique because it targets cognitive, white-collar tasks—unlike previous industrial revolutions which primarily automated manual or physical labor.

The Mechanism of Job Displacement: Task Substitution

Job displacement occurs when a machine system successfully performs a discrete set of tasks that previously required human cognitive effort. Crucially, entire jobs are rarely eliminated at once; rather, the most routine tasks within a job are substituted by technology.

The vulnerability of a job is defined by its reliance on routine, predictable tasks. Roles involving predictable data entry, document classification, basic customer service inquiries (via chatbots), or rudimentary financial analysis are highly susceptible. For example, a paralegal’s task of sorting thousands of discovery documents can now be executed by a language model in minutes. This doesn't eliminate the paralegal role, but it reduces the demand for the low-value administrative component of their work.

This task substitution has several immediate consequences:

Skill Polarization: Automation disproportionately impacts middle-skilled, medium-wage roles (e.g., clerical workers, production supervisors) because those tasks are often routine enough to be algorithmic. Low-skill roles requiring physical dexterity or human-centric services (e.g., gardening, elderly care) remain harder to automate, while high-skill roles requiring complex judgment are augmented.

Productivity Shock: The automation of routine tasks significantly increases the efficiency of the firm. A customer service agent, relieved of answering 80% of repetitive queries, can now handle more complex or emotional customer issues. This productivity gain can lead to higher firm profits and, potentially, lower consumer prices, which stimulate demand and create new jobs elsewhere in the economy—a core tenet of the historical "compensation effect."

The Engine of Job Creation: The Three A's

While the displacement effect is immediate and tangible, the job creation effect is more subtle and takes longer to materialize. New employment opportunities emerge primarily through three pathways.

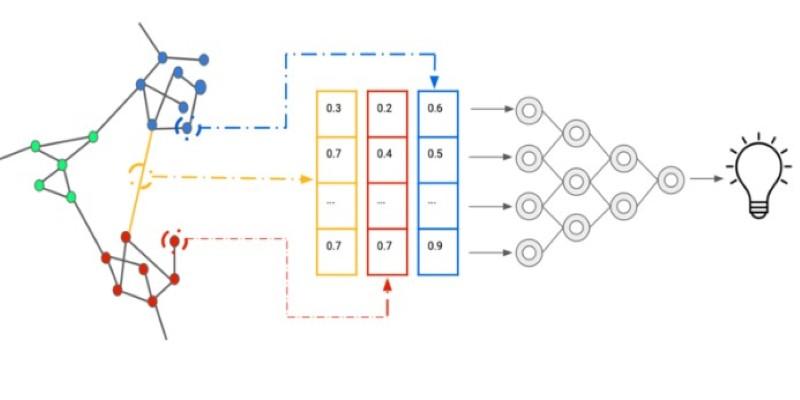

1. Augmentation: The Complementary Role

Many jobs are not replaced, but radically restructured. Automation serves as a co-pilot, enhancing human capability rather than substituting it. A radiologist, for example, is not replaced by an image recognition model; the model rapidly flags potential abnormalities, allowing the radiologist to focus their limited time and expertise on the most complex cases. New roles are created by this augmentation:

Human-Machine Teaming Managers: Professionals dedicated to optimizing the workflow between a human worker and their machine partner, ensuring effective communication and task hand-offs.

Prompt Engineers: Specialists who learn how to effectively query and guide advanced generative models to achieve specific, high-quality, and reliable outputs.

2. Activation: New Economic Activity

Automation often drives down the cost of a product or service so dramatically that demand explodes, requiring more human labor to meet the new scale. The development of sophisticated computational tools has created entirely new economic sectors and job categories that were unimaginable two decades ago:

Data Curators: Professionals dedicated to cleaning, labeling, and organizing the massive, high-quality datasets required to train and maintain automated systems.

AI Ethicists and Compliance Managers: Roles established specifically to audit algorithmic outputs, identify and mitigate systemic bias, and ensure the deployment of computational systems adheres to evolving legal and ethical frameworks.

3. Administration: The Infrastructure of Automation

Every automated system requires a vast human infrastructure to be built, maintained, and governed. This creates entirely new technological support roles:

Machine Learning Engineers: The primary architects who design, develop, and deploy the probabilistic models.

AI Infrastructure Developers: Engineers focused on building and maintaining the massive specialized hardware (e.g., GPU clusters, distributed servers) necessary for model training and inference.

AI Training Specialists: Human workers who specialize in training and refining early-stage models using techniques like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).

The Crucial Challenge of Transition and Inequality

Historical economic analysis generally concludes that, over the long term, technological innovation creates more jobs than it destroys. However, this macro-economic optimism offers little comfort to the individual worker facing immediate displacement.

The true challenge is one of transition and inequality. The skills being displaced (routine clerical work, simple data processing) are not the same as the skills being created (advanced data science, ethical governance). This mismatch leads to structural unemployment, where displaced workers lack the education or resources to transition into the newly created roles. This gap exacerbates wealth polarization, as the financial rewards accrue disproportionately to the highly skilled technical experts and the capital owners of the automated infrastructure.

Policymakers and educators must proactively address this misalignment. Investments in flexible, high-quality upskilling and reskilling programs are essential to bridge the talent gap. Education must pivot away from rote knowledge and toward uniquely human skills—creativity, complex strategy, cross-cultural empathy, and critical judgment—skills that remain fundamentally difficult for current systems to replicate.

Conclusion: A Shift in Human Value

Advanced automation is not leading to the "end of work," but rather a dramatic and necessary redefinition of what constitutes valuable human labor. The technology acts as a powerful lever, amplifying human output in high-judgment tasks while systematically eliminating the need for routine cognitive effort.

The future labor market will demand that workers move "up the value chain," shifting from tasks that involve simple execution to tasks that require oversight, ethics, creativity, and personal connection. The economic impact of automation will ultimately be determined not by the capability of the technology itself, but by the effectiveness of human institutions—education systems, governments, and corporations—in managing this inevitable structural transition with foresight, compassion, and speed.