The most crucial goal in modern medicine is moving the focus away from simply fixing problems after they start, toward preventing them entirely. Right now, the most powerful tool making this shift happen is advanced computational systems—the smart technology that crunches data—giving doctors and healthcare providers the ability to look ahead and predict future risks.

These systems work by consuming massive amounts of health information—everything from patient records and genetic codes to imaging and daily activity patterns. They find tiny trends and risk factors that the human eye would almost certainly miss. This capability is revolutionary: it allows doctors to forecast conditions like diabetes or heart disease well before any symptoms appear, making proactive care possible and ultimately saving lives.

Predictive Analytics: Forecasting the Future of Health

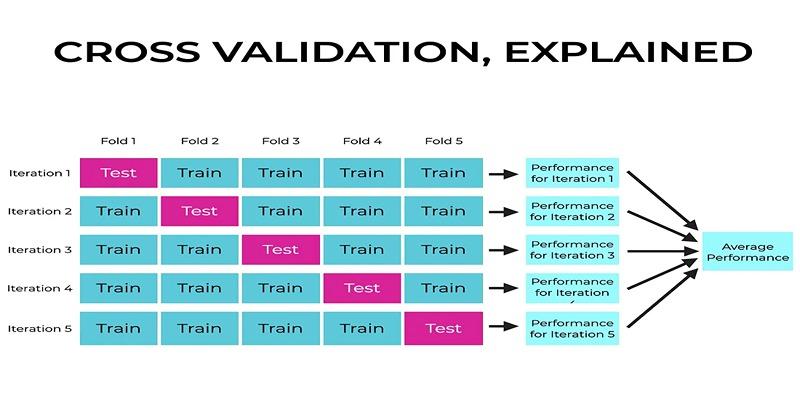

The core mechanism for early risk detection is predictive analytics. This involves using mathematical models to analyze historical data and make accurate forecasts about an individual's future health outcomes.

Risk Stratification and Personalized Care

Predictive models are used to group patients based on their potential health risks.

Identifying High-Risk Individuals: Algorithms analyze various factors—age, genetics, lifestyle habits, and medical history—to create comprehensive risk profiles. The system then assigns a precise risk score that predicts the likelihood of events like disease onset or hospital readmission.

Resource Allocation: This process, known as risk stratification, allows healthcare systems to prioritize resources and interventions for those most at risk. For example, high-risk patients might receive personalized care plans and immediate, tailored follow-up, ensuring resources are used where they have the greatest impact.

Genomic and Genetic Data Analysis

Analyzing an individual's unique genetic code is crucial for predicting hereditary risks.

Finding Hidden Markers: Computational systems can analyze complex genomic data to identify mutations or patterns that signal a predisposition to chronic diseases like cancer or cardiovascular disease. The sheer volume and complexity of DNA sequences make this analysis impossible without computational assistance.

Tailored Prevention: By identifying these markers early, the system allows for the development of highly personalized medical plans and preventative strategies tailored to the patient's genetic profile.

Instant Pattern Recognition in Visual and Text Data

Sophisticated computational techniques are used to analyze unstructured and highly complex data types that traditionally required extensive human labor.

Image-Based Diagnostics (Computer Vision)

The use of computer vision allows models to interpret and make decisions based on visual data, accelerating the detection of conditions that are best seen.

Early Cancer Detection: Algorithms trained on millions of images (mammograms, CT scans, MRIs) can detect tumors, tiny irregularities, or abnormal patterns with high accuracy. For example, systems have been shown to detect breast cancer earlier and with greater precision than traditional methods.

Diabetic Retinopathy: Computational models can examine retinal scans to identify early signs of diabetic retinopathy, which, if caught early, can prevent blindness in diabetes sufferers.

Extracting Insights from Clinical Notes (NLP)

Electronic Health Records (EHRs) contain rich, but often disorganized, free-text data in doctor's notes and clinical literature.

Natural Language Processing (NLP): NLP enables the system to interpret and understand this human language. It extracts valuable insights, symptoms, and subtle risk indicators from this unstructured text, which might otherwise be overlooked, providing a more comprehensive view of the patient's history.

Real-Time Monitoring and Proactive Intervention

The medical industry is shifting data collection out of the isolated clinic and directly into the patient’s daily life. Historically, doctors relied on "episodic" data—measurements taken only during scheduled appointments. This approach leaves massive blind spots, as a patient’s condition can deteriorate significantly in the weeks or months between visits without any medical oversight.

To close this gap, modern protocols utilize remote sensors and continuous monitoring tools. These are not just consumer fitness trackers; they include clinical-grade devices like continuous glucose monitors, adhesive cardiac patches, and connected pulse oximeters. These instruments capture vital signs 24/7, providing a complete, high-resolution picture of a patient’s physiology as they sleep, work, and exercise.

This continuous stream allows the system to establish a precise baseline for "normal" behavior specific to that individual. Rather than waiting for a patient to report symptoms, the software identifies deviations the moment they occur. If heart rate variability drops or blood pressure trends upward over three days, the system flags the anomaly. This allows care teams to make small, preventative adjustments to medication or lifestyle immediately, preventing the expensive, dangerous emergency room visits that result from ignoring these early warning signs.

Wearables and Remote Monitoring

Wearable devices and sensors collect continuous data on vital signs, heart rate, and activity patterns.

Anomaly Detection: Systems analyze this real-time data stream, identifying subtle variations in a person's baseline health metrics that could be potential precursors to an infectious disease or a chronic condition onset. This acts as an early warning system, allowing individuals and clinicians to intervene proactively.

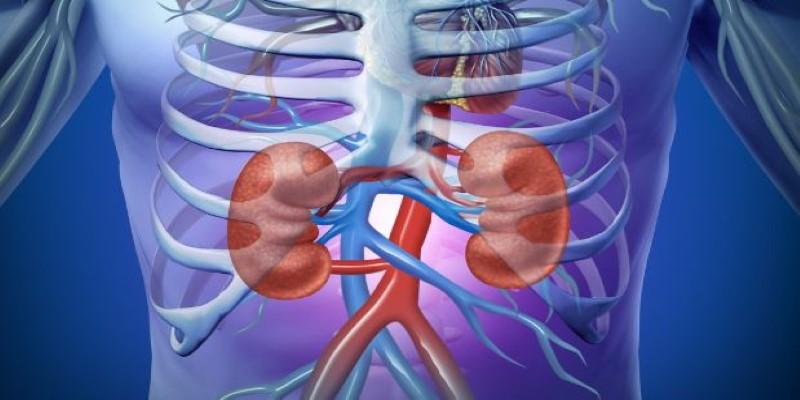

Acute Injury Prediction: Models have been developed to predict acute conditions, such as acute kidney injury (AKI), up to 48 hours before clinical symptoms appear, allowing clinicians crucial time to intervene and prevent progression.

Public Health and Outbreak Forecasting

The technology is also used for large-scale, preventative public health measures.

Early Warning Systems: By integrating health data with environmental factors (like climate, which impacts vector-borne diseases), systems can predict where and when infectious disease outbreaks (such as Dengue or Zika) could occur. This provides public health officials with lead time to mobilize resources and implement preventative measures.

Conclusion

The successful application of computational systems in healthcare is rapidly redefining early detection and preventative care. By harnessing the power of predictive analytics, computer vision, and the synthesis of vast, multi-modal data, these tools can identify subtle disease markers and accurately forecast future health risks years in advance. This capability allows healthcare providers to shift from a reactive mode—treating symptoms after they appear—to a proactive mode, intervening with personalized preventative measures. The true value of this technology is not just in detection, but in the revolutionary potential of prevention.